No products in the cart.

Filling in the Blanks

Ewart Oakeshott’s typology may be one of the most useful tools in documenting and understanding the Medieval arms race, but it is far from a complete picture of the development of the Medieval sword. In order to complete one’s picture of the sword, one must also look at the hilts of the sword, and even the decoration of the blade. Oakeshott recognized this, and his work not only covered his typology, but also linked the swords in it to blade inscriptions and hilt forms.

Ewart Oakeshott’s typology may be one of the most useful tools in documenting and understanding the Medieval arms race, but it is far from a complete picture of the development of the Medieval sword. In order to complete one’s picture of the sword, one must also look at the hilts of the sword, and even the decoration of the blade. Oakeshott recognized this, and his work not only covered his typology, but also linked the swords in it to blade inscriptions and hilt forms.

The Military Relic

The knightly sword was far more than just a weapon to the Medieval knight. It was also a religious object, a personal sanctified cross that the knight would carry into battle. And, its blade decorations reflect this.

Inlays on blades were nothing new in the 12th century. For centuries before, the Ulfberht and Ingelrii sword firms had been marking their products with their names inlayed along the fuller, as had other smiths. In the 11th century, the type X swords began to show a distinction in their decoration – while one side of the sword still bears the maker’s name, the other was inlayed with a religious inscription. The most common was “INNOMINEDOMINI” (“In the name of God”), although this is often misspelled. There were also variations – a type X sword in Dresden has an Ingelrii inlay on one side, and on the other, in small neat letters, the words “HOMODEI” (“Man of God”), which Oakeshott suggests means that the sword was made for a crusader.

By the time the type XI swords appear, the smith’s name in the inlays had disappeared – the writing on both sides

of the sword were now for God. “INNOMINEDOMINI” remained a common inscription, but it was joined by other inlays, such as “BENEDICTUS DEUS MEUS” (“God bless me”) and “SES PETRNUS” (“Blessed/Saint Peter”).

The 13th century saw these inlays become even more sophisticated, and in some cases symbolic to the point of becoming difficult to understand. A late example of a type X has ornately drawn letters spelling “SOSMENCRSOS” – Oakeshott suggests the “OS” probably stands for “O Sancta” (“O holy”), the “M” is probably “Maria,” the “CR” is likely “Christus,” and the EN “Eripe Nos” (“Save us”), leaving the entire inlay a version of “O holy Mary and Christ save us.”

These religious inlays – of increasing sophistication and complexity – continued well into the 13th century before personal marks again began to appear, with bladesmiths marking their work with a maker’s mark such as a bull’s head or a wolf.

However, these inscriptions also started to fall out of fashion by the 14th century. Some inlays still appeared, but they were far simpler than they once had been, and by the middle of the 14th century, the inlay was for all intents and purposes no longer in use. Maker’s marks still appeared, but sword blades after the 14th century were usually void of decoration. It is difficult to say why this trend of inscriptions came to an end, although there are certainly possibilities – by the Hundred Years War, sword blades were being provided to the English army in bulk, suggesting that the time required to carry out an inlayed inscription was no longer profitable in the production of swords. Also, the inlays disappear as the sword ceases to be solely a knightly weapon of war, and becomes something used also by the infantry and for judicial duels – it may be that the sword had lost its status as a holy object by the 14th century, and become just another weapon.

Hilts and Sword Families

Categorizing swords by their hilts is nothing new – prior to Oakeshott’s typology, this was the way that historians tended to categorize swords. Oakeshott’s work shone a much-needed light on the importance of the blade, but he also recognized that the hilts and furnishings of a sword were important enough to warrant further examination.

Oakeshott’s own understanding of how hilts could be best understood took time to develop – in his Archaeology of Weapons, he outlines a number of different types of pommels and guards, and provides examples, but he doesn’t take it further. It was in The Records of the Medieval Sword that Oakeshott developed his idea of sword families, a unifying principle that took the vast number of variations in sword fittings and categorized them in such a way that one can understand how the style of the sword developed over time, as well as date a sword and sometimes even determine its place of origin.

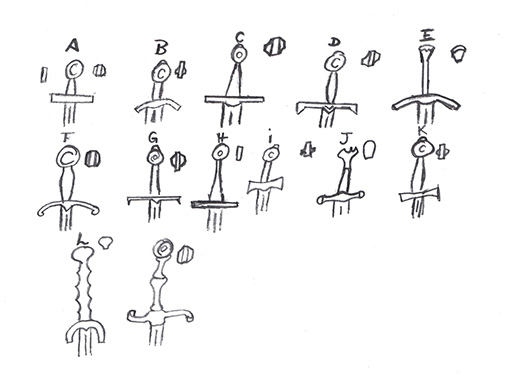

Oakeshott outlined 13 different sword families, naming them with the letters “A” to “M.”

The first family, Family A, is perhaps the most widely seen of them all. Swords in this family appear throughout the period from 950 onwards, but are at their most popular between 1050-1300. Just about everybody who has seen Medieval swords has seen this family – a short grip, disc or wheel pommel, and straight cross.

Family B is localized both in time and its sword blade, in this case the type XIV. This family appears between 1280-1325, and has a thin cross arched towards the blade, a short handle, and a wheel pommel with a prominent boss.

Family C is similar to Family A, but has a longer grip and a deep wheel pommel. Most of the type XIIIa swords fit into this family, which also has a very long period of representation – although it most commonly appears between 1250-1360, early representations of this family go back as far as 1100.

Family D appears between 1360-1410. The length of the grip remains the same, but the hilt is far more ornate. The wheel pommel now has a recessed hollow in its central boss, and the guard is very distinctive – it is long, often thicker in the middle, tapers down towards the ends, and the tips angle downward towards the blade at a 90 degree angle.

With Family E, we begin to see the development of a new pommel. This is a 14th century sword family, with its two most notable examples belonging to Austrian knights – this family is called the “Sempach” type, named after the battle in which the knights fell. The handle is long, the guard curving towards the blade but without any narrowing, and the pommel is a truncated wedge, its arched upper area filed down into anywhere between four and six hollow “scallops,” as Oakeshott describes it.

Family F is one of the more famous types of Medieval sword. It appears mainly from 1410-1550, and is a single-handed variant. It has a large wheel pommel, and a distinctive and elegant guard – the cross is long and ribbon-like, arching towards the blade with ends that are either rolled or scrolled over, and a peak in the middle towards the blade.

Family G is very similar to Family F, and while the two families do overlap in their dating, it appears early enough that it may also serve as a precursor – this sword family is mainly represented between 1380-1440. The primary difference between the two families is the guard, which is very similar to Family D. Considering the similarities and dating, it is possible that this family was a single-handed variant of Family D that appeared after it became popular.

Family H has the distinction of being perhaps the only family of swords that Oakeshott didn’t like – he writes that it is “ugly,” “dull,” “lifeless,” and “undistinguished.” The family itself has a simple hilt, with a long, straight guard, a long handle, and a flat disc pommel, often with a small recess in the center. This was, however, a popular sword, and its period of usage spans around 300 years, from the early 13th to the early 16th centuries.

With Family I, we come to a sword family that can be dated in both time and place – in this case, Southern Europe in the 14th century. This is a single-handed sword family, with a bow tie shaped guard and a large disc pommel that has an outstanding central boss. This sword family is also associated with a particular type of blade: broad, flat, and with narrow fullers. These swords do not tend to appear in art, but a number have been found in the arsenals of Constantinople and Alexandria.

Family J is a distinctive 15th century sword family mainly found in a discovery from Castillon. This single handed sword family was popular from 1420-1470, with a unique guard and pommel. The guard is short and narrow, with hemispherical knobs at its ends and a widened mid-point. The pommel is a long fish tail form, and appears to grow organically out of the top of the grip.

The next two families are from Denmark. Family K is a single handed sword, whose pommel is a flattened wheel, and whose guard is a bow tie shape similar to Family I. Family L is a 15th century variant of the long war sword – it has a very long handle with 4-5 horizontal ridges at regular intervals. Its pommel is pear-shaped, and its guard is short, flat, strongly arched towards the blade, and wider in the middle.

The final sword family, Family M, is a very common Northern European family used between the middle of the 15th century to the first quarter of the 16th century. It has a two-part grip and a long guard whose ends turn horizontally in an S-curve. The pommel is a wheel with a hollow recess.

Putting It All Together

Ewart Oakeshott’s impact on the study of arms and armor cannot be overestimated. With his work, Oakeshott provided the tools to illuminate the Medieval sword. With his typology, he brought to light a Medieval arms race that had remained hidden for centuries. With his examination of sword inlays, he revealed not just the shape of the sword, but its meaning to the men who wielded it. And, with his development of sword families, he created a further tool to help locate any given sword into its correct time and place.

Today, we have the ability to take any given Medieval sword and understand its time, place, purpose, and meaning to its owner. We owe this mainly to the extensive and life-long work of Ewart Oakeshott, to whom the field of sword studies will always be indebted.

Bibliography

Chad Arnow, Russ Ellis, Patrick Kelly, Nathan Robinson, and Sean A. Flynt, “Ewart Oakeshott: The Man and His Legacy: Part V.” MyArmoury.com, 2006: http://www.myarmoury.com/feature_oakeshott5.html

Ewart Oakeshott, The Archaeology of Weapons, Barnes & Noble Books, 1994 (originally published, 1960).

Ewart Oakeshott, Records of the Medieval Sword, The Boydell Press, 1991.