No products in the cart.

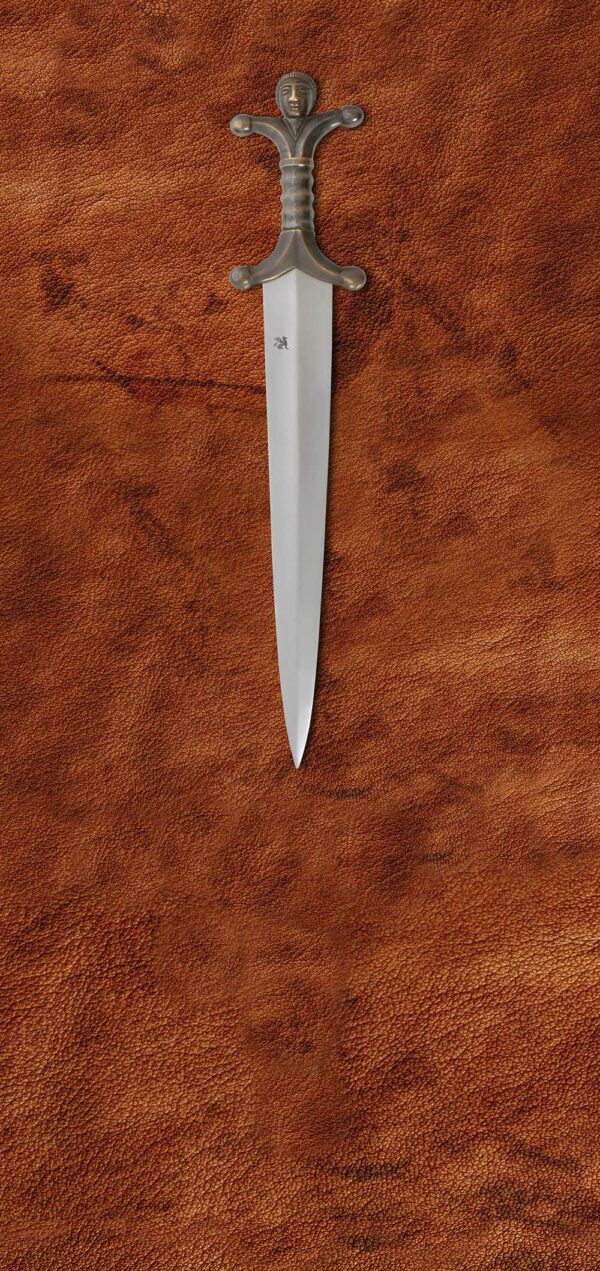

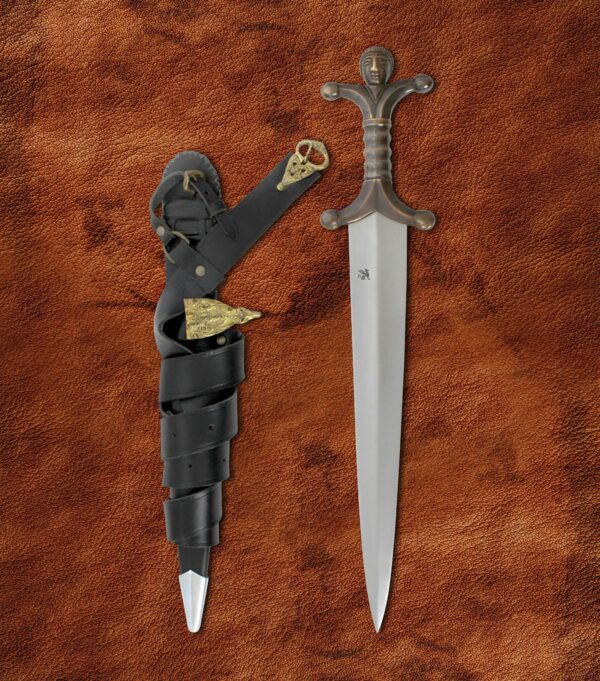

The Hastings (#1311)

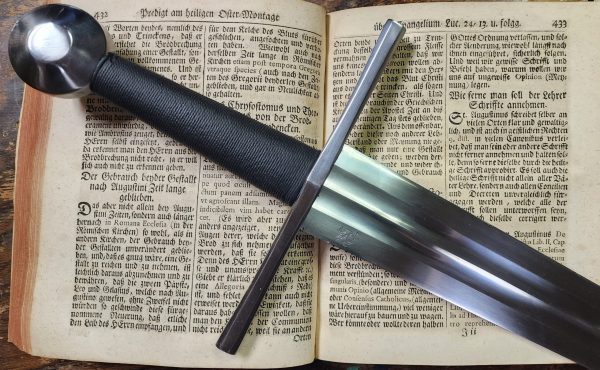

“The Hastings” is an elegant design fostered by the classic hand-and-a-half sword of the Noman knights. Inspired by an Oakeshott Sub-Type XIIIa, this version has a double fuller which extends to ¾ the length of the blade. The sword is named after the Battle of Hastings, one of, if not, the most important battles in English history. The Battle of Hastings took place on October 14th 1066, and marked the end of Anglo-Saxon rule in Britain as well as leading to the introduction of the common law.

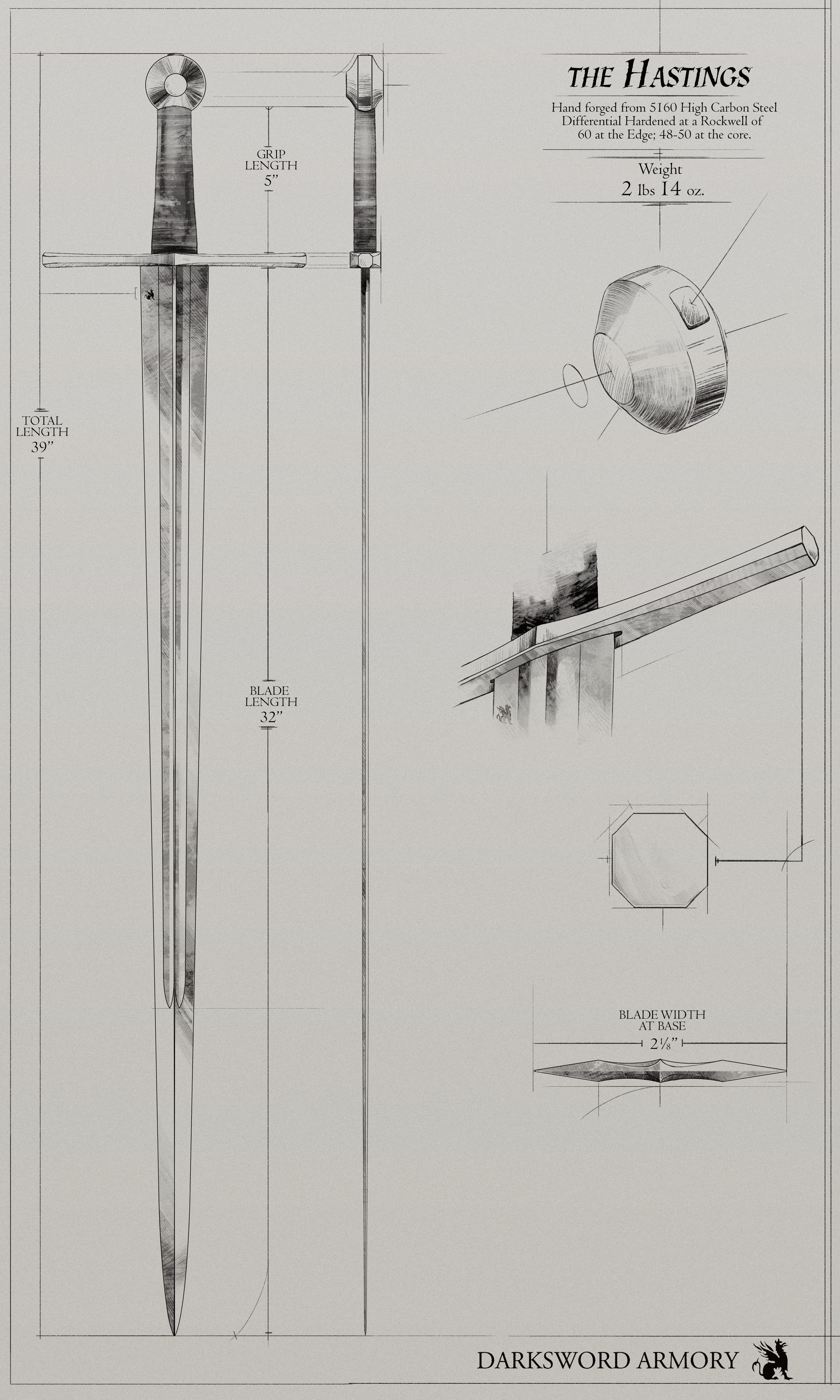

Hand forged from 5160 High Carbon Steel

Hand forged from 5160 High Carbon Steel

Differential Hardened at a Rockwell of 60 at the Edge; 48-50 at the core.

Fittings: Mild Steel

Handle: Leather Wrapped wood Core (oak)

Total length: 39″

Blade length: 32″

Blade width at base: 2 1/8″

Grip Length: 5 inches

Weight: 2 lbs 14oz

CAD847.61 – CAD1,029.74Price range: CAD847.61 through CAD1,029.74

SKU: N/A

Categories: Medieval Swords, New Products, One Handed Sword

It would be hard to overstate the difficulty in invading Britain. The historical home of the Anglo-Saxons, Britain was an incredibly challenging fortress to assault. Anyone wishing to make a concerted effort to invade the island would have to cross the English Channel with enough of a fighting force to subdue the not inconsiderable armies that could be raised from its inhabitants. Challenges with logistics, especially bringing food and other resources to support a large invading force, would make it difficult for any extended campaigns to be successful. And extended they would need to be – despite how it may seem to us now in the modern world, Britain is not a small island. Thus, for foreign invasion of the British Isles to be successful it would need to rely on decisive battles that both broke the defending forces and allowed a foothold to be gained by the invaders. And, on this Day in History in the year 1066, one such decisive battle occurred.

It would be hard to overstate the difficulty in invading Britain. The historical home of the Anglo-Saxons, Britain was an incredibly challenging fortress to assault. Anyone wishing to make a concerted effort to invade the island would have to cross the English Channel with enough of a fighting force to subdue the not inconsiderable armies that could be raised from its inhabitants. Challenges with logistics, especially bringing food and other resources to support a large invading force, would make it difficult for any extended campaigns to be successful. And extended they would need to be – despite how it may seem to us now in the modern world, Britain is not a small island. Thus, for foreign invasion of the British Isles to be successful it would need to rely on decisive battles that both broke the defending forces and allowed a foothold to be gained by the invaders. And, on this Day in History in the year 1066, one such decisive battle occurred.

William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy as of 1035 CE, was like the rest of Normandy descended from Viking stock. For William, though, he had a special connection to his Viking ancestors – he was a descendant of Rollo Sigurdsson, first king of the Normans. Perhaps it was this lineage that led William to the decision to invade England; although certainly his relation to Edward the Confessor (childless king of England, and William’s cousin) may have had something to do with it.

Some historians even believe Edward promised to make William his heir, even if word had promised to do so at one point this is not a promise he kept. On his deathbed in January 1066 the English king named Harold Godwinson, a powerful English noble, as his heir. William responded in a way that would have made his ancestors proud, and in early autumn of the same year landed a massive invasion force on the southeast coast of Britain. He quickly advanced to Hastings and began laying the foundation for his victory (including building a fortress to safeguard his beachhead).

King Harold, still fighting to retain his crown against local unrest, chose to march south in haste with what soldiers he could gather. His army of infantry with archers supporting the foot soldiers arrived at Hastings on October 13th, facing off against the Normans the next day. William, by contrast, had brought primarily cavalry with more archers then infantry. Battle was joined in the morning continued until dark that day with neither side gaining a definitive upper hand. Both kings fought with their armies, and by some accounts William’s horse died while he was fighting not once, not twice, but three times. The battle could have raged for days had not Harold been slain in the melee, with no clear account of how he fell. When the Anglo-Saxon forces realized their king was dead, their lines broke and they fled.

William would face only token resistance from then on, and would be crowned King of England on Christmas Day of that year. All of which happened because of the turning point at Hastings.

The Darksword Armory Hastings Sword is a bastard sword with a unique appearance. The cruciform guard is similar to most surviving examples of medieval swords for several centuries, and the thick wheel pommel (weighted to give the sword a nimble heft and swing) is close in design to other swords of the era. We chose a black leather wrap and scabbard to accent the bright, satin-finished steel. Where this sword stands out most, though, is in its blade design. Like similar swords from the Oakeshott Sub-Type XIIIa family, the Hastings has a long, broad, double-edged blade suitable for the cut-and-thrust combat of the 13th- and 14th- centuries. This sword, though, has crisp a double fuller that extends ¾ the length of the blade. This fuller gives the Hastings a distinctive, noble appearance, a cut above the standard arming sword of the average soldier.

Be the first to review “The Hastings (#1311)” Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Related products

Fantasy Swords

Rated 4.5 out of 5

CAD952.68 – CAD1,176.84Price range: CAD952.68 through CAD1,176.84Rated 4.8 out of 5

CAD847.61 – CAD1,029.74Price range: CAD847.61 through CAD1,029.74Medieval Swords

Rated 5 out of 5

CAD651.47 – CAD693.50Price range: CAD651.47 through CAD693.50Fantasy Swords

Rated 5 out of 5

CAD917.66 – CAD1,141.82Price range: CAD917.66 through CAD1,141.82Medieval Swords

Rated 5 out of 5

CAD875.63 – CAD1,260.90Price range: CAD875.63 through CAD1,260.90Fantasy Swords

CAD728.52 – CAD868.62Price range: CAD728.52 through CAD868.62

This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page Broadsword

Rated 4.67 out of 5

CAD798.57 – CAD1,225.88Price range: CAD798.57 through CAD1,225.88Medieval Swords

Rated 5 out of 5

CAD742.53 – CAD945.68Price range: CAD742.53 through CAD945.68Arming Swords

Rated 5 out of 5

CAD791.57 – CAD1,008.72Price range: CAD791.57 through CAD1,008.72Arming Swords

Rated 5 out of 5

CAD826.59 – CAD1,001.72Price range: CAD826.59 through CAD1,001.72Fantasy Swords

Rated 5 out of 5

CAD945.68 – CAD1,169.84Price range: CAD945.68 through CAD1,169.84HEMA Swords, WMA Swords and Weapons

Rated 5 out of 5

CAD350.25

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.