No products in the cart.

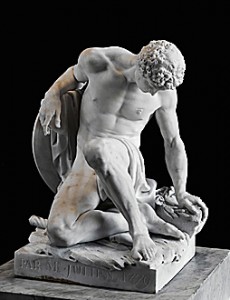

Gladiators, originating from the Latin word “gladius” or sword, stemmed from professional and amateur fighters in ancient Rome who fought for the entertainement of “civilized” spectators. Gladiators were trained in special schools called ludi which could be found as commonly as ampitheatres throughout the empire. There were four schools in Rome itself, the largest of which was called the Ludus Magnuswhich was connected to the Coliseum by an underground tunnel. Among the most famous is the school at Capua where the slave rebellion of Spartacus was sparked in 73 BC. Typically, like modern boxers, most gladiators would not fight more than 2 or 3 times a year and with enough fame and fortune they could purchase their freedom. Some, however, such as criminals, were either expected to die within a year, or might earn their release after three years, if they survived.

Gladiators, originating from the Latin word “gladius” or sword, stemmed from professional and amateur fighters in ancient Rome who fought for the entertainement of “civilized” spectators. Gladiators were trained in special schools called ludi which could be found as commonly as ampitheatres throughout the empire. There were four schools in Rome itself, the largest of which was called the Ludus Magnuswhich was connected to the Coliseum by an underground tunnel. Among the most famous is the school at Capua where the slave rebellion of Spartacus was sparked in 73 BC. Typically, like modern boxers, most gladiators would not fight more than 2 or 3 times a year and with enough fame and fortune they could purchase their freedom. Some, however, such as criminals, were either expected to die within a year, or might earn their release after three years, if they survived.

Gladiator games, known as “ludi circenses”, took place in arenas of various sizes and prestige, throughout the empire. The ludi circenses, seen as a method to appease the Roman gods and avert Rome from disaster, were first fought in wooden arenas. The first stone built amphitheatre in Ancient Rome was the Amphitheater of Statilius Taurus (built in 29 BC), later to be followed by the Roman Colosseum, built in 80AD. The origin of the ludi circenses is rooted in the Estruscan custom of ritual human sacrifices to honor the dead. The first recorded gladiatorial fight took place in 264 BC, when three pairs of slaves were selected to fight as part of a funeral ritual called a munus. Similar games were organized by Julius Caesar, on the death of his daughter Julia,in which 320 paired gladiators

were made to fight. The concept of the munus was to keep the memories of ranking individuals alive after death.

In its earliest forms, individuals of patrician or equestrian status organized these, often to gain political favor with the public. The organizer of any of these ludi circenses was called the editor, munerator, or dominus and he was honored with the official signs of a magistrate, but the Emperors were nearly solely responsible for all public ludi circenses.

Gladiators were typically criminals, slaves, or prisoners of war. If selected for such duty, having lost, or never had, the rights of a citizen, there was no choice but to comply. Some Roman citizens willingly pledged themselves to the owner, or lanists, of a gladiatorial troupe, known as familia, by (according to Petronius) swearing an oath “to endure branding, chains, flogging or death by the sword”. It has been estimated that by the end of the Republic, about half of the gladiators were volunteers (auctorati), who took on the status of a slave for an agreed-upon period of time, similar to indentured servitude that was common in the late second millennium.

By taking the gladiator’s oath, the auctorati agreed to be treated as a slave and suffered the ultimate social disgrace. The potential advantages for this new career could outweigh the alternatives, however. Aside from the potential for public fame and fortune, including liaisons with Roman women, the gladiator recruit became a member of a cohesive group that was known for its courage, good morale, and absolute fidelity to its master to the point of death. Life became a model of military discipline and through courageous behavior he was also now capable of achieving honor similar to that enjoyed by Roman soldiers on the battlefield.

By taking the gladiator’s oath, the auctorati agreed to be treated as a slave and suffered the ultimate social disgrace. The potential advantages for this new career could outweigh the alternatives, however. Aside from the potential for public fame and fortune, including liaisons with Roman women, the gladiator recruit became a member of a cohesive group that was known for its courage, good morale, and absolute fidelity to its master to the point of death. Life became a model of military discipline and through courageous behavior he was also now capable of achieving honor similar to that enjoyed by Roman soldiers on the battlefield.

Contrary to modern portrayal, gladiatoral combat was less likely to result in

death than is imagined. Gladiators were expensive to maintain, train and replace in the event of death, and keeping the most popular of crowd pleasers alive was far more practical than the alternative. That’s not to say, however, that death wasn’t common among the non-elite. In these cases, when a gladiator had overpowered his opponent, he would turn to the spectators for a reaction from the crowd. The defeated gladiator would possibly raise his left hand (also sometimes referred to as raising a finger which may have indicated a request for mercy) asking for his life to be spared. If the spectators turned their thumbs down they were indicating that the fighter should live (perhaps indicating a desire to sheath or lay down the weapon). One theory regarding the thumbs up is that it represented the desire for the victor to cut his opponents throat. Other suggestions include the crowd yelling ‘missum‘ or ‘mitte‘ (release or send away) as a gesture of mercy, or alternatively yelling ‘iugula‘(kill) when they wanted the victor to finish his opponent.

There are other theories regarding the use of thumbs and various motions to indicate the end of a match, such as that the thumb was positioned sideways to indicate a slashing

There are other theories regarding the use of thumbs and various motions to indicate the end of a match, such as that the thumb was positioned sideways to indicate a slashing

motion across the neck, or even that a thumb pointed down with a thrusting motion may have represented an order for the victor to thrust his sword down into his opponents chest. Regardless of the debated hand motions, the final decision in this was not made by popular crowd appeal and was usually left to a single judge (though clearly abiding by the crowd’s desire was a wise policy). In the presence of the Emperor, the judgment belonged to him, but otherwise it may rest with the games munerator or sponsor.

Gladiatoral contests came to a close in 325 AD, when first outlawed by Constantine I and then by Emperor Honorius. The last known gladiator competition in the city of Rome occurred on January 1, 404.

Facts about Gladiators

- The first recorded gladiatorial fight was staged in 264AD when three pairs of slaves who were selected to fight at the funeral of a prominent Roman

- The word ‘Gladiator’ was derived from Gladius which was the Latin word for sword

- Gladiator games were seen as a method to appease the Roman gods and avert Rome from disaster

- Gladiatorial combats were first fought in wooden arenas. The first stone built amphitheatre in Ancient Rome was called the Amphitheater of Statilius Taurus was built in 29 BC. The Roman Colosseum was built in 80AD Nearly 30 types of gladiators have been identified

- The role of the Gladiator became big business in the Roman Empire. Political careers could be launched on the back of spectacular games. Large sums of money could be won by gambling on the outcome of gladiator fights

- The games organised by Julius Caesar, on the death of his daughter Julia, featured 320 matched pairs

- Roman courts were given the authority to sentence criminals to death fighting as gladiators

- Slaves, criminals and prisoners of war were forced into the roles of the first gladiators

- By the period of the Roman Empire free men started to enrol as gladiators. Some were ex- soldiers, some wanted the adulation and the glory and some needed money to pay their debts. A Free gladiator was called Auctorati

- Gladiators were allowed to keep any prizes or gifts they were given during gladiatorial games

- Entrance to the gladiator games was free but spectators, between 50,000 – 80,000 were issued with tickets

- Trainee gladiators were called Tirones or Tiro

- Female Gladiators, some noble and wealthy, appeared in the arenaBestiarii (Beast Fighters) were the gladiators who fought wild animals

- The Praegenarii were the ‘opening act gladiator’. This type of gladiator only used wooden swords, accompanied to festive music.

- Elite types of Gladiators were the Rudiarius who were gladiators who had obtained their freedom but chose to continue fighting in gladiatorial combats

- Gladiatorial schools “Ludi Gladiatorium”. The gladiator schools also served as barracks, or in some cases prisons, for gladiators between their fights.

- New Gladiators were formed into troupes called ‘Familia gladiatorium’ which were under the overall control of a manager (lanista)

- At the end of the day the gladiators who had been killed were dragged through the Porta Libitinensis (Gate of Death) to the Spoliarium where the body was stripped and the weapons and armor given to the dead gladiator’s lanista.

- Prospective gladiators (novicius) had to swear an oath (sacramentum gladiatorium) and enter a legal agreement (auctoramentum) agreeing to submit to beating, burning, and death by the sword if they did not perform as required .

- Gladiators often had tattoos (stigma, from where the English word stigmatised derives) applied as an identifying mark on the face, legs and hands.

- Trained gladiators joined formal associations, called collegia, to ensure that they were provided with proper burials and that compensation was given to their families.

- The early enemies of Rome included the Samnites, the Thracians and the Gauls (Gallus) and gladiators were named according to their ethnic roots

- Gladiators were always clothed and armed to resemble barbarians with unusual and exotic weapons and their fights depicted famous victories over barbarians and the power of the Roman Empire

- One of the most famous gladiator was the Emperor Commodus (177-192 AD) who boasted that he was the victor of a thousand matches. The Roman Emperors Caligula, Titus, Hadrian, Cracalla, Geta and Didius Jalianus were all said to have performed in the arena.

- The Emperor Honorius, decreed the end of gladiatorial contests in 399 AD

- The last known gladiator fight in the city of Rome occurred on January 1, 404 AD.

Northern England Roman Gladiator excavation site